Subtitle to this blog entry: The Toilet Travails of Traveling.

We were meant to leave Paris immediately after an early breakfast but the tour bus was over an hour late fighting its way through city traffic. I think that meant we were officially on French time. It was a wet and miserable morning so most of us were crammed into our hotel lobby. We occupied ourselves reading and chatting. I had thought to bring along the flowers my beloved had sent me but the peonies were wilting, as peonies quickly do. My lovely flowers weren't going to survive the trip so while we were waiting, I donated them to the lobby restroom and took one final photo. Adieu!

As we finally drove away, I spied from the bus window a commemorative plaque honoring a man named Robert Jacques Houbré, a Résistance fighter with the rank of Sergeant in the French Forces of the Interior (Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur, aka FFI). Houbré, age 43, was mortally wounded on August 22, 1944 on this spot at the corner of Boulevard Saint-Michel and Rue de Vaugirard, and he was awarded the Croix de Guerre posthumously. This isn't far from the major intersection of Blvds St-Germain and St-Michael, a corner notoriously known as the Carrefour de la Mort during the intense seven day battle to liberate Paris. Some of the fiercest fighting took place in this area. Parisians blocked their streets to the Germans by building homemade barricades, a tradition in times of strife dating back to the 16th century. Houbré's plaque is also around the corner and down the street a bit from the Palais du Sénat at the Jardins du Luxembourg, where desperate fighting to wrest control of Le Senate took place. Clearly Robert Jacques Houbré was in the thick of things, but I have not been able to trace the details of M. Houbré's story.

Someone must still know it though, because a floral arrangement had been left to honor his memory. I found myself wishing that I still had a peony left from my arrangement to add to it. I've long been fascinated by the small and large acts of heroism of everyday folks who participated in La Résistance française during World War II. This plaque prompted quiet reflection about that time as our bus got underway.

Someone must still know it though, because a floral arrangement had been left to honor his memory. I found myself wishing that I still had a peony left from my arrangement to add to it. I've long been fascinated by the small and large acts of heroism of everyday folks who participated in La Résistance française during World War II. This plaque prompted quiet reflection about that time as our bus got underway.

|

Robert Jacques Houbré memorial |

The farther we drove out of Paris, the better the weather got. Wendy and I occupied ourselves with meandering chitchat. It was a long drive to Falaise, about 115 miles.

Necessity soon dictated that I was to be the one to inaugurate the bus loo, which was neatly concealed under a seat in the back stairwell. A succession of women (our tour group was comprised of 30 women and 3 men) followed me, and unfortunately it soon became obvious that there was, well, mechanical trouble. We were scolded for not discarding waste paper in its proper receptacle as the signs...in French...clearly told us we were to do. Pity someone in the party who could actually decipher French toilet instructions hadn't used the loo first!

To add insult to indignity, when our bus pulled over at a rest stop the only loos available were Turkish squatters. I'd come across these twice before, in Egypt and outside of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire Abbey near Orléans. I didn't think I'd find one at a roadside rest stop

in Normandy, but it makes sense given the low maintenance involved. There was much appalled muttering from our group over this contrivance. I later learned that Googling 'squatter toilet' provides much fascinating trivia regarding the history and usage of these devices, including instructional videos. The best piece of advice: "Use your hand

sanitizer and remind yourself that travel is all about broadening your

horizons."

To add insult to indignity, when our bus pulled over at a rest stop the only loos available were Turkish squatters. I'd come across these twice before, in Egypt and outside of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire Abbey near Orléans. I didn't think I'd find one at a roadside rest stop

in Normandy, but it makes sense given the low maintenance involved. There was much appalled muttering from our group over this contrivance. I later learned that Googling 'squatter toilet' provides much fascinating trivia regarding the history and usage of these devices, including instructional videos. The best piece of advice: "Use your hand

sanitizer and remind yourself that travel is all about broadening your

horizons."

Obligatory rest stop photo:

I was vastly amused while waiting at this pit stop to spy our driver leaving the bus gingerly carrying a large tree branch complete with leaves, which he'd apparently used as a plunger to attempt rudimentary toilet repair.

One does what one must, and makes do.

Driving through the Val d'Ante valley, by mid-afternoon we had our first sighting from the bus window of the fortress of Falaise. It rose majestically out of the limestone and sandstone hillsides. I think everyone on the bus gasped in unison.

This fortress at Falaise occupies the site of the castle built by William the Conquerer and later greatly expanded by Eleanor's Henry. Proof of human presence in this area dates back to 60000 years BCE and fortifications on the rocks have existed since the Carolingian era (mid 10th century). The original castle was built by Richard I, Sans Peur (great-grandfather of William the Conquerer and 4x great grandfathe

The tall tower to the right is the Talbot Tower (built by Philippe Auguste, who had a thing for towers) and the Great Keep. Henry I built the keep over the first ancestral castle in the style of those built in England by his father, William the Conqueror.

It was time for lunch but as it was the French countryside, all restaurants were closed in mid-afternoon. I'd been wondering if that would be the case, based on previous experiences with this phenomenon. In smaller towns and villages of France, you can pretty much count on everything closing for lunch and not reopening until mid-afternoon -- which was right when we'd arrived in Falaise. Some of us wandered through Place Guillaume le Conquérant to Rue du Camp Ferme where we found a small marché and stocked up on croissants, cheeses and fruit (and begged the proprietress to let us clog, I mean use, her small bathroom). We took lots of photos along the way as we then made our way up to the castle.

Necessity soon dictated that I was to be the one to inaugurate the bus loo, which was neatly concealed under a seat in the back stairwell. A succession of women (our tour group was comprised of 30 women and 3 men) followed me, and unfortunately it soon became obvious that there was, well, mechanical trouble. We were scolded for not discarding waste paper in its proper receptacle as the signs...in French...clearly told us we were to do. Pity someone in the party who could actually decipher French toilet instructions hadn't used the loo first!

To add insult to indignity, when our bus pulled over at a rest stop the only loos available were Turkish squatters. I'd come across these twice before, in Egypt and outside of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire Abbey near Orléans. I didn't think I'd find one at a roadside rest stop

in Normandy, but it makes sense given the low maintenance involved. There was much appalled muttering from our group over this contrivance. I later learned that Googling 'squatter toilet' provides much fascinating trivia regarding the history and usage of these devices, including instructional videos. The best piece of advice: "Use your hand

sanitizer and remind yourself that travel is all about broadening your

horizons."

To add insult to indignity, when our bus pulled over at a rest stop the only loos available were Turkish squatters. I'd come across these twice before, in Egypt and outside of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire Abbey near Orléans. I didn't think I'd find one at a roadside rest stop

in Normandy, but it makes sense given the low maintenance involved. There was much appalled muttering from our group over this contrivance. I later learned that Googling 'squatter toilet' provides much fascinating trivia regarding the history and usage of these devices, including instructional videos. The best piece of advice: "Use your hand

sanitizer and remind yourself that travel is all about broadening your

horizons."Obligatory rest stop photo:

I was vastly amused while waiting at this pit stop to spy our driver leaving the bus gingerly carrying a large tree branch complete with leaves, which he'd apparently used as a plunger to attempt rudimentary toilet repair.

One does what one must, and makes do.

Driving through the Val d'Ante valley, by mid-afternoon we had our first sighting from the bus window of the fortress of Falaise. It rose majestically out of the limestone and sandstone hillsides. I think everyone on the bus gasped in unison.

|

| Photo by Susan Taksa O'Dee |

This fortress at Falaise occupies the site of the castle built by William the Conquerer and later greatly expanded by Eleanor's Henry. Proof of human presence in this area dates back to 60000 years BCE and fortifications on the rocks have existed since the Carolingian era (mid 10th century). The original castle was built by Richard I, Sans Peur (great-grandfather of William the Conquerer and 4x great grandfathe

The tall tower to the right is the Talbot Tower (built by Philippe Auguste, who had a thing for towers) and the Great Keep. Henry I built the keep over the first ancestral castle in the style of those built in England by his father, William the Conqueror.

It was time for lunch but as it was the French countryside, all restaurants were closed in mid-afternoon. I'd been wondering if that would be the case, based on previous experiences with this phenomenon. In smaller towns and villages of France, you can pretty much count on everything closing for lunch and not reopening until mid-afternoon -- which was right when we'd arrived in Falaise. Some of us wandered through Place Guillaume le Conquérant to Rue du Camp Ferme where we found a small marché and stocked up on croissants, cheeses and fruit (and begged the proprietress to let us clog, I mean use, her small bathroom). We took lots of photos along the way as we then made our way up to the castle.

|

| Photo by John Phillips showing the whole of Place Guillaume le Conquérant |

In the year 911, Viking chief

Rollo signed a peace treaty with the King of Franks which created the

Duchy of Normandy, and in honor of that event and to promote tourism Normandy was celebrating its 1100th anniversary in 2011. These banners were all over Falaise.

The creation of the dukedom of Normandy (the land of the north) ushered in a new political scene. The town of Falaise became one of the first cities of the new duchy. Fast forward a millennium and two-thirds of the town was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1944 during

World War II. Some older charming buildings like these still remain, though not from Eleanor's time!

Falaise was a center of commerce in Eleanor's time due to linen, hemp and woolen drapery, leatherwork, and farming in the surrounding countryside. Today it has about 8000 residents.

Also in the town square was Eglise de la Trinité. The original church was built

around the year 840, and thus would have been known by Eleanor. It was destroyed during the siege of Falaise by Philippe Auguste in 1204 when he wrested control away from Eleanor and Henry's

youngest son, John. The present church dates from the 1400-1500s:

We were drawn to this statue of William the Conqueror on a very big horse. It was sculpted by Louis Rochet in 1851, and two decades later statues representing the preceding six dukes of Normandy were added to the base. Those other six were Rollo, William I Longue Épée (Longsword

|

| Guillaume le Conquérant |

William was born in 1028 at Falaise Castle. He was the illegitimate son of the 6th Duke of Normandy Robert le Magnifique (also known as le Diable or the Devil for presumably killing his brother). His mother Herleve (most often called Arlette) was the daughter of Fulbert of Falaise. Before his conquest of England, William was known as The Bastard because of the illegitimacy of his birth. Despite those regrettable circumstances, he was named heir to Normandy by his father. William had to deal with all manner of challenges to his birthright but had secured it by the time he was 19. He married his distant cousin Mathilda of Flanders in 1053, and they had ten children. In 1066, William took advantage of a dispute over the succession of the English throne, crossed the Channel, and invaded at Hastings. After a fierce battle lasting nine hours, William defeated Harold Godwinson. He marched to London and was crowned Christmas Day 1066 in Westminster Abbey, the first documented coronation held there. (Harold Godwinson may have been crowned in Westminster earlier that year, making him the first, but there's no contemporary evidence to support this so I'm going with the Bastard on this one).

Eleanor's second husband Henry was the great-grandson of William. That legacy loomed large over the Plantagenets, who considered themselves Norman and not English. Falaise is only 20 miles south of Caen, which was one of the places I dearly wished we could have visited in order to pay our respects at the burial sites of William the Conquerer and his consort Matilda of Flanders.

Eleanor's second husband Henry was the great-grandson of William. That legacy loomed large over the Plantagenets, who considered themselves Norman and not English. Falaise is only 20 miles south of Caen, which was one of the places I dearly wished we could have visited in order to pay our respects at the burial sites of William the Conquerer and his consort Matilda of Flanders.

This monument to testosterone inspired Wendy to organize the future Bastard Tour of France and England. We're still waiting on the complete itinerary (Caen is one of the stops for sure) but in the meantime some of us adopted a name for ourselves after admiring this statue: The Bastard Babes.

We finally tore ourselves away from Bill the Bastard's sculpted manliness and headed to Château de Falaise, Château Guillaume le Conquérant

|

| Photo by Malcolm Craig |

When Eleanor's youngest son John lost Normandy to France's Philippe Auguste, Falaise fell during the Siege of Château-Gaillard in 1204. Once it was his, Philippe added the many semi-circular towers and the Talbot Tower. I told you he had a thing for towers, which served to defensively flank the curtain walls. The castle fell from

French control during the Hundred Years' War in 1418, and was occupied by

the English for 32 years until recaptured by King Charles VII.

During the Wars of Religion in the late 1500s, Falaise was held by Catholics who refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of the King Henri IV (remember that we previously discussed his skull). Henry IV laid siege to the castle from near-by Mount Myrrha and breached the ramparts with cannon. That was the end of an era for Falaise Castle, as it was no longer significant defensively.

In the 18th century Château de Falaise passed into private hands and underwent many alterations so it could function as an aristocratic residence. Over time the castle moats and ditches were filled. Amazingly it escaped destruction during the Revolution. The castle was officially classified as a Historical Monument in 1840, and the first restoration effort took place in 1863 by a student of Viollet-le-Duc.

During the Wars of Religion in the late 1500s, Falaise was held by Catholics who refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of the King Henri IV (remember that we previously discussed his skull). Henry IV laid siege to the castle from near-by Mount Myrrha and breached the ramparts with cannon. That was the end of an era for Falaise Castle, as it was no longer significant defensively.

In the 18th century Château de Falaise passed into private hands and underwent many alterations so it could function as an aristocratic residence. Over time the castle moats and ditches were filled. Amazingly it escaped destruction during the Revolution. The castle was officially classified as a Historical Monument in 1840, and the first restoration effort took place in 1863 by a student of Viollet-le-Duc.

These youngsters were leaving after a field trip and had paused for a photo op. I could just imagine my own 7 year old son up there with them. Feeling briefly maternally melancholic, I headed to the castle itself.

The center forebuilding which houses the reception and gift shop was constructed in 1996 by architect Bruno Decaris, who undertook an ambitious campaign of restoration beginning in 1986. He restored the Talbot Tower and the keeps, and built this structure to evoke the feel of classic forebuildings of Anglo-Norman keeps. Decaris used all modern materials in the parts of the castle where there were no traces of original materials, choosing to do so in order to evoke but not mimic the missing features. The forebuilding was controversial because the choice of modern grey concrete in a building of this size was criticized for disrupting the cohesive look of the castle

grounds. However controversial, the building is in keeping with the UNESCO guidelines

for architectural interventions to historical edifices. There would have been a drawbridge here, which is evoked by the suspended metal footbridge.

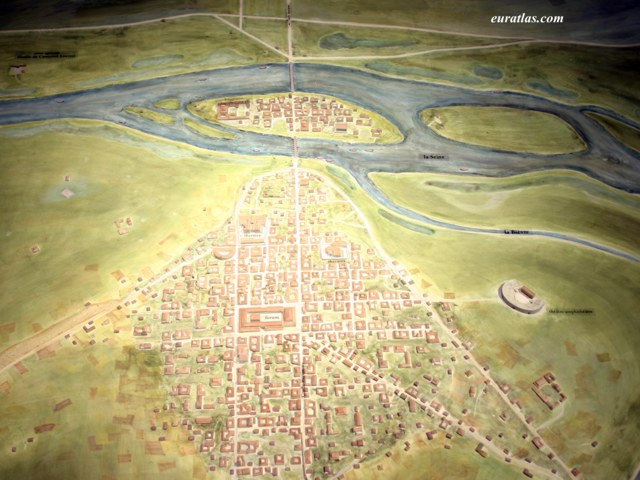

Inside we found a model of the early castle showing how it looked in Eleanor's time.

Inside we found a model of the early castle showing how it looked in Eleanor's time.

Henry built the lower keep with later additions by sons Richard and John during their reigns.

Sharon Kay Penman told us that Falaise was one of Henry's favorite castles and an important base of operations for him. We know for sure that Henry and Eleanor held their Christmas court at Falaise castle in 1159. A room on the upper floor of the Lower Keep, with these odd IKEA-like thrones, is meant to evoke the Great Hall where the court was held. It's an awfully small room for that purpose. Eleanor is depicted to the left in this photo of the Great Hall.

Sharon Kay Penman told us that Falaise was one of Henry's favorite castles and an important base of operations for him. We know for sure that Henry and Eleanor held their Christmas court at Falaise castle in 1159. A room on the upper floor of the Lower Keep, with these odd IKEA-like thrones, is meant to evoke the Great Hall where the court was held. It's an awfully small room for that purpose. Eleanor is depicted to the left in this photo of the Great Hall.

Sharon thought it very likely that Henry held Eleanor prisoner at Falaise after the family rebellion of 1173, before whisking her off for her long confinement in England.

We came across a fun display of the hierarchy of power and privilege in the Middle Ages, from Roi down to the lowly paysans et serfs. This hierarchy directly corresponds with how comfortable one's life would be. Falaise had many of these modern educational elements and judging by the rapt attention of the visiting children, it was all quite effective.

|

| Photo by John Phillips |

The visiting children no doubt enjoyed seeing this medieval garderobe. Mine would have, at any rate, and no doubt would have staged a posed photo op.

We walked around the grounds of Falaise and tried to imagine a younger Eleanor and Henry here in happier days. The view from the walls of the surrounding landscape was breath-taking and I imagined it to be a vista untouched by time, a scene not unlike what Eleanor might have seen when she stayed at Falaise.

Unmodified archer loop and/or ventilation slit to the left, probably circa 13th century. Modified archer loop with cannon holes to the right; the holes were added by the English occupiers in the 15th century to accommodat

Peeking from the upper bailey to the town of Falaise below.

|

| Photo by Susan Taksa O'Dee |

I have to admit that some of architect Bruno Decaris' 'evocative' modern materials gave me pause. For instance, this grating was used for flooring outside the keep and was easily one hundred feet above ground. It made me shriek with horror when I first realized what I was standing on, startling my fellow tour members. Sorry about that, folks!

After that, I decided not to venture to the top of Talbot Tower and settled for admiring it from a distance.

Philippe Auguste's Tour Talbot is similar in design to the towers that he built for his arsenal at the medieval Louvre, which we saw yesterday. The tower is 115 feet

tall with a diameter of 49 feet. It had six levels with wooden ceilings

and stone-ribbed vaults. Light and ventilatio

Great resource to learn more about Château Guillaume le Conquérant can be found at this website: LINK.

The second phase of modern renovation, from 1998-2003, was focused on restoring the upper rampart and courtyard of the castle. The third phase, evident by the ubiquitous scaffolding that we'd passed on our way up to the castle, is aimed at restoring the defensive character through further work on the ramparts, enclosure towers, and

ditch.

I applaud all efforts at historical preservation. Restoration is a noble and welcome endeavor. But there is still something compelling about a ruin.

As we straggled back to our bus, Tee and I spied this charming chocolatier and of course a visit and some purchases occurred. Our loot helped pass the time on the next leg of our journey.

From Falaise, we crossed part of the area known as the Suisse Normande (Norman Switzerland) on our way to Mont St-Michel. I squealed internally every time we passed these vache charolaise!

|

| Photo by Nicole Benkert |

Next stop: Mont-St-Michel.

Sharon Kay Penman's blog entry about our tour of Falaise and subsequent arrival at Mont St-Michel can be found here: LINK

.jpg)